Obol Network and Distributed Validator Technology: Decentralizing Ethereum's Security Infrastructure

For crypto-native audiences, investors, and institutional stakers, the question is no longer whether DVT will matter—it's whether your validators will run on it

The emergence of Distributed Validator Technology (DVT) represents a fundamental shift in how Ethereum’s consensus layer can scale while preserving decentralization. As staking centralization threatens network security and restaking multiplies slashing risks across the ecosystem, Obol Network offers a middleware-based solution that allows multiple independent operators to jointly run a single validator without compromising security or performance. This article explores the technical architecture of DVT, its application to liquid staking protocols, and why it has become critical infrastructure for the restaking era.

The Problem With Today’s Validator Architecture

Centralization of Node Operators

Ethereum’s transition to Proof of Stake has created an unintended consequence: validator infrastructure has become increasingly concentrated among a handful of large entities. Lido Finance alone controls approximately 31% of all staked Ethereum, while a few institutional staking providers command the majority of validation duties. This concentration emerged not from design but from economic incentives—the capital, technical expertise, and infrastructure required to run validators efficiently create strong returns to scale, making it difficult for smaller participants to compete.

The problem is not merely that Lido dominates; it’s that the network’s security now depends on the operational reliability of a small number of organizations. If a major staking service experiences a simultaneous outage across its validator infrastructure—whether due to a bug in client software, a cloud provider failure, or a malicious attack—a meaningful portion of Ethereum’s validator set could go offline at once. Unlike decentralized mining in Proof of Work, where individual miners can adjust their participation independently, Proof of Stake creates systemic correlation risks when validators use the same client software, run on the same cloud infrastructure, or operate from the same geographic regions.

Single-Operator Failure Risks

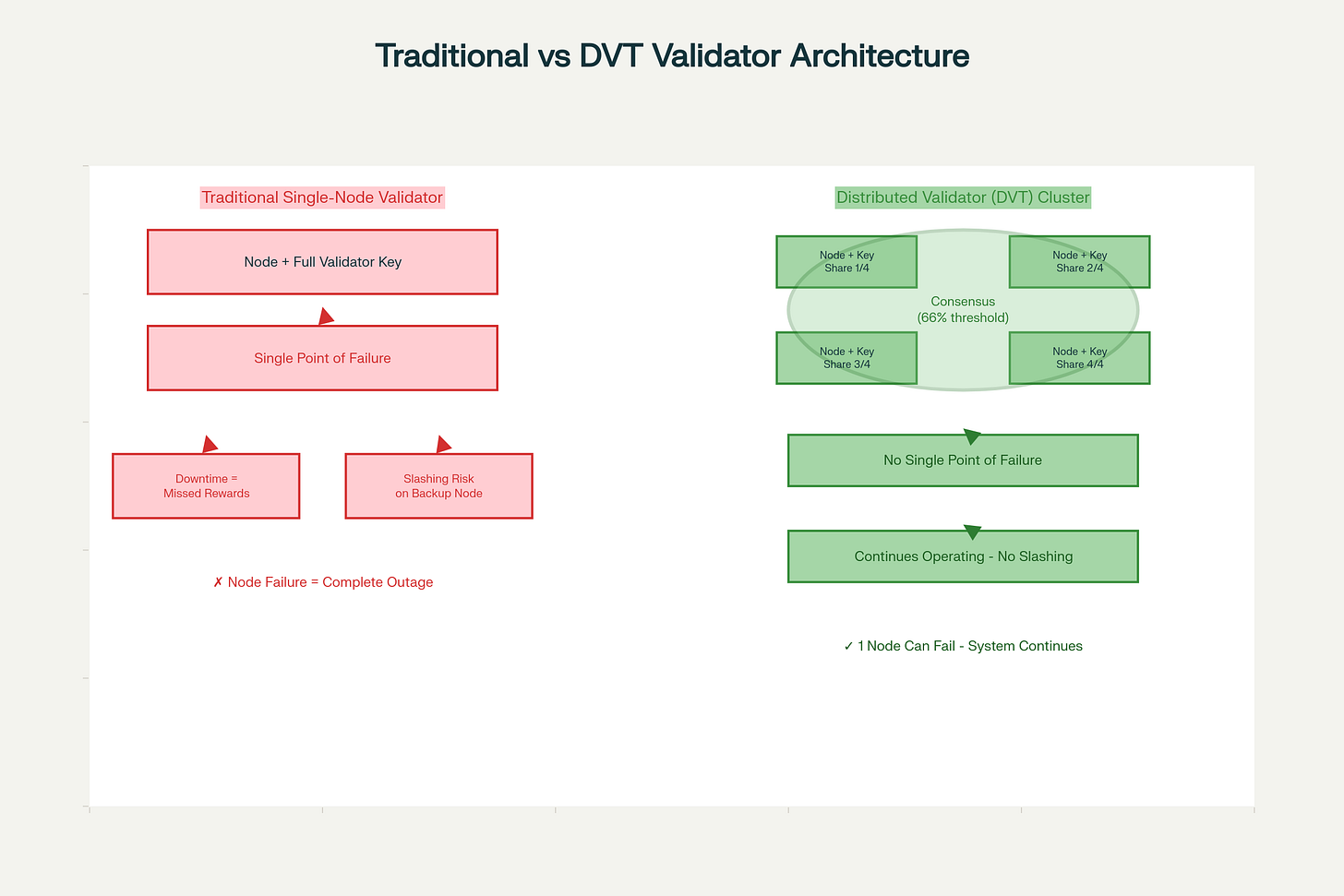

Traditional validator operation inherently relies on a single node or a tightly coordinated set of nodes under one operator’s control. When a validator runs on a single machine, there is no redundancy; machine failure means validator downtime. To mitigate this, larger operators employ active-passive setups—running a backup validator that can be activated if the primary fails. However, this approach introduces its own critical vulnerability: the double-signing problem.

In Ethereum’s Proof of Stake model, if a validator signs the same message twice using the same key, the network treats this as provable misbehavior and can slash up to 100% of the validator’s staked ETH. When transitioning from a primary to a backup validator, coordinating the shutdown and activation of these nodes is challenging. Misconfiguration, monitoring failures, or network delays can result in both nodes attesting simultaneously—incurring immediate and severe penalties. This risk means that smaller validators cannot safely run backups and must accept downtime as an operational reality, while larger institutions absorb the costs of sophisticated monitoring and coordination infrastructure that smaller participants cannot justify.

Increased Systemic Risk From Liquid Staking and Restaking

The proliferation of liquid staking protocols (Lido, Rocket Pool, StakeWise) and restaking platforms like EigenLayer has exacerbated these problems rather than solving them. Liquid staking protocols delegate validator management to a small set of node operator partners, creating a two-layer centralization problem: first at the liquid staking protocol level, then at the node operator level. While protocols like Lido have increased their operator count to over 200 operators, the permissioned nature of joining these protocols creates barriers that maintain centralization pressure.

Restaking, which allows already-staked ETH to provide security to additional services (Active Validator Services, or AVSs), introduces a new dimension of risk. When a validator is restaked across multiple AVSs, the validator faces slashing risk on each service independently, and these risks may be correlated—meaning that the same operator mistake or infrastructure failure could trigger slashing on multiple services simultaneously.

Correlated Slashing Risk Across AVSs

Research on restaking risk demonstrates that correlation is often a more significant factor in ruin risk than the raw probability of slashing on any single AVS. If multiple AVSs share validation clients, run infrastructure from the same cloud providers, or are operated by the same network of node operators, a single failure can cascade across all of them. For example, if a majority of Ethereum’s restakers operate through a handful of institutions and those institutions experience a simultaneous outage or software bug, the cost to the network could be extraordinary—not just in lost capital, but in broken security guarantees to downstream services.

Current estimates suggest that in scenarios with 10 or more AVS commitments and high correlation in slashing events, ruin risk accelerates dramatically. This represents an existential problem for the restaking ecosystem: AVS developers want to scale their security guarantees, but the concentration of validator infrastructure creates the very centralization risk they’re trying to mitigate.

What Obol Network Is Trying to Solve

Introducing Distributed Validator Technology (DVT)

DVT is a middleware layer that allows a single Ethereum validator to be operated by multiple independent nodes simultaneously, without requiring a central trusted party and without increasing slashing risk. Instead of one node holding the complete validator private key, DVT splits the key into encrypted shares—each held by a different operator—such that the full key never exists in any single location.

The fundamental insight behind DVT is that validator duties can be divided into components that multiple parties can perform independently, then combined using cryptographic techniques to produce valid signatures. This is conceptually analogous to multisig wallets for validators: just as a multisig requires multiple signatures to execute a transaction, a distributed validator requires multiple operators to reach consensus on each attestation and proposal.

By distributing validator duties in this way, Obol and other DVT providers solve the centralization problem at its root: instead of trusting one operator’s infrastructure, stakers can distribute trust across a diverse set of independent operators, each maintaining their own nodes in different geographic locations and cloud providers.

How Sharing Validator Duties Increases Resilience

The key innovation is that a distributed validator can maintain full operational capacity even if some operators go offline, as long as the threshold of active operators is met. With a 7-out-of-10 cluster configuration, for example, the validator can continue operating normally even if 3 operators experience downtime simultaneously.

This is fundamentally different from a backup node setup. In traditional active-passive configurations, the backup is only activated if the primary fails—creating a binary decision with high risk. In DVT clusters, all nodes are active simultaneously in an “Active-Active” redundancy configuration. Each node independently listens for its validator duties, processes them, and when enough nodes have reached consensus, they collectively generate a valid signature. If one node is temporarily slow or offline, the others continue without interruption.

This architectural shift has profound implications for smaller validators and protocols. Community validators and at-home operators can now achieve the same availability guarantees as large institutions by pooling resources with other operators in a DVT cluster—without requiring the capital investment or technical sophistication of maintaining sophisticated backup infrastructure.

How Obol Works: Simple First, Then Technical

Distributed Validator Clusters (DVCs)

An Obol Distributed Validator Cluster consists of 4–10 independent operators (typically), each running their own node in different locations. These operators are usually unaffiliated and may not trust each other directly—but the protocol ensures that they cannot break network rules without economic or cryptographic consequences.

To form a cluster, operators must agree on several parameters: the threshold (e.g., 7 out of 10), which clients to run, the network configuration, and the cluster’s governance rules. This group then runs a Distributed Key Generation (DKG) ceremony, a cryptographic ritual that generates the cluster’s validator key shares.

Once the ceremony completes, each operator receives:

Their private key share (encrypted and stored locally)

A cluster definition file that all operators possess

Validator deposit data (the public key and deposit credentials needed to activate the validator on Ethereum)

The entire group then deposits 32 ETH to activate the validator on the Ethereum beacon chain. All the participants now collectively own and operate this validator.

The Charon Client

The technical magic happens through Charon, Obol’s open-source middleware written in Go. Charon acts as an intermediary layer between each operator’s Ethereum validator client (Lighthouse, Teku, Prysm, Nimbus) and their beacon node.

Charon’s primary job is to intercept consensus messages and coordinate with other Charon instances in the cluster to reach agreement on validator duties. When Ethereum assigns the cluster’s validator a duty (e.g., propose a block at slot 1000, or attest to a block at epoch 250), Charon instances communicate via a peer-to-peer network to decide how to respond collectively.

The communication overhead is minimal—Charon uses approximately 10–50 kilobytes per second in typical mainnet deployments. Each Charon instance connects to the others via relay servers (facilitating NAT traversal) or direct P2P connections (preferred for lower latency), using the libp2p protocol standard.

Distributed Key Generation (DKG)

DKG is the cryptographic ceremony that enables DVT to work without a central key generator. In a traditional setup, one party generates the validator key and distributes shares—creating a single point of failure and requiring trust in that party. Pedersen’s DKG eliminates this trust requirement.

In Pedersen’s scheme, each operator contributes a random secret, and these secrets are combined to produce the final validator key. Crucially, no single operator learns the complete key; each only learns their own share. The protocol ensures that participants cannot cheat by submitting invalid shares—any attempt to do so is cryptographically detectable and can be rejected.

The mathematical foundation relies on Shamir’s Secret Sharing, a threshold cryptography scheme where a secret is divided into N shares such that any K shares can reconstruct the secret, but fewer than K shares reveal nothing about the secret. In a 7-of-10 configuration, any 7 of the 10 key shares can generate valid signatures, but no subset of 6 or fewer can.

How Consensus Among Operators Happens

Once a DVC is operational, consensus happens through a Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) algorithm, typically Istanbul BFT (IBFT) or Quorum Byzantine Fault Tolerance (QBFT). These protocols were originally designed for permissioned blockchains but work well for coordinating a small group of known validators.

Here’s the flow:

Duty Assignment: Ethereum’s beacon chain assigns a duty to the validator (e.g., “propose a block”). All Charon instances in the cluster see this duty.

Leader Election: The BFT protocol designates one node as the leader (proposer) for this duty. If the leader is offline or acts maliciously, the protocol automatically rotates leadership to another node within ~12 seconds.

Consensus Round: The leader proposes how to respond to the duty. Other nodes validate this proposal and vote on it. Once more than 66% of nodes agree (in most configurations), the decision is finalized.

Signature Creation: Each node creates a partial BLS signature using their key share. These partial signatures are combined using threshold BLS aggregation to produce a valid Ethereum signature.

Submission: The aggregated signature is submitted to Ethereum as if it came from a single validator.

If any node in the cluster goes offline, the remaining nodes continue this process as long as the threshold is met. If 34% or more nodes are offline in a 7-of-10 cluster, consensus fails until nodes come back online, but no slashing occurs—Ethereum only penalizes validators for misbehavior, not downtime.

Why DVT Matters Now: The Restaking Era

Restaking Multiplies Slashing Risks

EigenLayer introduced restaking, which allows stakers to allocate already-staked Ethereum to provide security to new services (AVSs). A single staker can be re-secured to 5, 10, or 15 different AVSs simultaneously. While this efficiently mobilizes Ethereum’s security, it creates a compound risk problem: each AVS represents an independent slashing condition, and if a validator misbehaves or goes offline while supporting an AVS, it faces independent penalties.

Research shows that the risk of cascading failures across AVSs is substantial. A 2025 analysis by Gauntlet found that correlation in slashing events across AVSs can contribute more to ruin risk than the baseline probability of any single AVS slashing. This means that if validator infrastructure is centralized—whether through Lido’s node operators, cloud providers, or shared client software—a single failure can trigger simultaneous slashing on multiple AVSs.

DVT Reduces Correlated Downtime and Operator Concentration

By distributing validator duties across geographically dispersed operators running different client implementations and cloud providers, DVT drastically reduces correlation risk. If one operator’s infrastructure experiences an outage, the DVC continues operating normally, and no operator or infrastructure failure can trigger network-wide penalties.

This is particularly important for restaking. A liquid restaking token (LRT) like Eigenlayer’s liquid restaking tokens can now accept deposits knowing that the underlying validator infrastructure is resilient and decentralized. Instead of all LRT validators being operated by Lido’s 40 node operators (concentrated), they can be operated by clusters where each operator is independent.

Empirical data supports this benefit: As of January 2025, Obol-secured validators achieved a 98.23% RAVER score (an industry metric for validator effectiveness), outperforming competitor solutions. This performance is not despite the coordination overhead—it’s because operators in DVT clusters are incentivized to maintain high-quality infrastructure to avoid letting down their co-operators.

Strengthens Security Guarantees for AVSs and LSTs

For AVS developers, DVT provides a critical guarantee: the slashing conditions they define will be enforced against genuinely independent validators, not a coordinated subset of the network. If an AVS requires that validators maintain some commitment (stake locked up, specific client version, etc.), that commitment is backed by the actual distribution of validator infrastructure, not illusory diversity that breaks under stress.

For liquid staking protocols, DVT enables a new operational model. Instead of centralizing risk among a few permissioned node operators, protocols like Lido can now onboard many more independent operators who run DVT clusters. Lido has already expanded from 36 operators to over 200 operators, with a significant portion now using Obol’s DVT. This transforms the security model from “trust the top 40 operators” to “trust that at least one of 200+ diverse operators will remain operational.”

Real Use Cases

Liquid Staking Protocols

Lido has formally integrated Obol DVT into its Curated Module—the pool containing ~90% of Lido’s TVL. Major operators like ParaFi Tech, DSRV, and Stakely have migrated their validators to Obol DVT clusters, securing billions of dollars in staked ETH.

StakeWise V3 has made DVT a core feature of its architecture, allowing vault operators to choose between Obol and SSV for DVT services, and enabling smaller operators to run isolated vaults secured by DVT.

Rocket Pool, traditionally focused on permissionless solo staking, has also integrated DVT to allow node operator collectives to coordinate without central governance overhead.

The adoption pattern is clear: every major liquid staking protocol recognizes that DVT is essential for the next phase of Ethereum staking—expanding operator diversity while maintaining network resilience.

EigenLayer AVS Operators

EigenLayer’s AVS operators are among DVT’s most active users. By running validators in DVT clusters, AVS operators significantly reduce their contribution to correlated slashing risk across multiple AVSs. An operator supporting 10 different AVSs can now distribute that risk across a 7-of-10 cluster, meaning no single infrastructure failure triggers slashing on all 10 services simultaneously.

Early EigenLayer AVSs have begun requiring or incentivizing operator participation in DVT clusters as a condition for accepting high validator stake. This creates a virtuous cycle: AVSs demand DVT for security, which drives adoption, which proves the model works, which accelerates institutional adoption.

Institutional Staking Desks

Large institutions—exchanges, custodians, and dedicated staking platforms—benefit substantially from DVT. Instead of building redundant backup systems in-house, institutions can join DVT clusters operated by trusted staking infrastructure providers.

Bitcoin Suisse, for example, uses Obol-powered validators for large portions of its Ethereum staking operations. This allows Bitcoin Suisse to offer high-availability staking without doubling hardware and staffing costs.

For institutions holding more than $100 million in staked ETH, the cost savings of DVT compared to traditional active-passive backup setups can exceed $1 million annually in avoided infrastructure and insurance expenses.

Risks & Open Questions

Performance Overhead

DVT introduces network coordination overhead—Charon instances must communicate to reach consensus on each validator duty. Current deployments target peer-to-peer latency below 235 milliseconds and consensus duration under 1 second, with optimal high-scale deployments achieving <25ms latency and <100ms consensus time.

In practice, this overhead is minimal and often undetectable compared to the time Ethereum allows for block proposals (~12 seconds from slot start to slot deadline). However, MEV-Boost integration has historically created challenges, as MEV-Boost adds its own latency, and coordinating across multiple Charon instances introduces complexity.

Recent Charon improvements (v0.18.0+) have reduced these issues significantly, and mainnet deployments consistently achieve 95%+ proposal success rates. As Charon matures, this overhead will likely continue declining.

Coordination Complexity

Running a DVT cluster requires operators to coordinate decisions—not just technically, but organizationally. How should operator fees be split? What happens if an operator wants to leave the cluster? How should upgrades be scheduled? How should consensus thresholds be set?

These are not technical problems but governance problems. Early DVT clusters often involve trusted parties who know each other, but as DVT scales, clusters will need to function among non-trusting operators who only know each other through smart contracts and economic incentives.

This coordination problem is solvable—multisig DAOs, smart contract-managed treasuries, and algorithmic governance can handle it—but it requires more infrastructure and clearer standards than currently exist.

Governance and Operator Incentive Alignment

As Obol distributes governance tokens (OBOL) to incentivize participation in DVT clusters, questions emerge about long-term incentive alignment. If OBOL tokens are primarily valuable as rewards for running DVT, will the incentive structure attract the right operators, or will it attract mercenary capital that leaves when rewards decline?

Furthermore, restaking and DVT create a new layer of economic complexity. An operator might earn MEV, priority fees, base rewards, OBOL incentives, and AVS rewards simultaneously. Optimizing across these competing incentives is non-trivial, and poorly aligned incentives could lead to adversarial behavior.

The solution is not technical perfection but robust market structures that reward reliable operators and penalize corner-cutting—standards that the ecosystem is still developing.

Conclusion: DVT as a Foundational Layer for Ethereum’s Next Phase

Distributed Validator Technology is not a minor optimization—it is foundational infrastructure for the next chapter of Ethereum’s evolution. As Proof of Stake matures and the network reaches billions in staked capital across restaking and liquid staking protocols, the concentration of validator infrastructure has become the network’s most critical vulnerability.

Obol Network’s approach—a permissionless middleware layer enabling operators to run validators in resilient clusters—addresses this vulnerability without requiring protocol-level changes. By distributing validator duties across independent, geographically dispersed operators, DVT simultaneously:

Reduces centralization, enabling thousands of smaller operators to achieve the availability and efficiency of large institutions

Mitigates slashing risk, particularly critical in the restaking era where validators face compound slashing conditions

Strengthens security, ensuring that AVS developers and liquid staking protocols can credibly commit to distributed validator infrastructure

Enables institutional adoption, removing the infrastructure burden that previously made Ethereum staking accessible only to the most well-capitalized participants

The evidence is already present in mainnet deployments: $975 million worth of ETH is now secured by Obol Distributed Validators, with adoption accelerating among Lido operators, EigenLayer AVS teams, and institutional staking providers. This represents not the peak of adoption but the early phase of a structural shift in how Ethereum validators operate.

For crypto-native audiences, investors, and institutional stakers, the question is no longer whether DVT will matter—it’s whether your validators will run on it. In the restaking era, DVT is not optional; it’s the baseline expectation for credible, decentralized Ethereum infrastructure.